A friend asked whether Listen Like a Lawyer has ever blogged on this:

Do men and women listen differently?

That’s an interesting—and fraught—question.

Some websites and popular books on communication skills propound appallingly simplistic statements with no research support. And the research on gender and listening that does exist has been described as “scarce and inconsistent.” (This is Laura Janusik surveying the literature up to 2007.) Still, the research is based not on speculation or stereotypes, but on a variety of actual studies with real participants (often college students, more on that later). And the results of this research serve to challenge overly simplistic beliefs about sex and gender.

FYI, the articles cited in this blog post are listed at the end. The information in this post focuses on listening generally or in professional settings, not in personal relationships. This is a very long post but it’s intentionally combined into one post so that the “nature” and “nurture” points can be taken together in context rather than in isolation. And the post tries to maintain the terminology of sex for biological differences and gender for psychological/self-identified/cultural roles.

Here is a simple takeaway if you don’t want to go through the rest, from a 2003 article by Virginia Tech professors Stephanie Sargeant and James Weaver:

Despite the popular reception of gender asymmetry in the way we talk with, listen to, and interact with one another, considerable research suggests that sex differences may actually play only a minimal role. Canary and Hause efficiently summarize the literature when they conclude, after considering hundreds of studies represented in meta-analyses, “sex differences in social interaction are small and inconsistent; that is, about 1% of the variance is accounted for and these effects are moderated by other variables.”

(Intrusive citations have been omitted from this quote.)

If that’s all you need to hear, now’s a good time to stop reading. The rest of the post goes into some various more specific gender-related findings on hearing and listening.

Hearing

The first step in listening is hearing. And this is where the strongest sex-related difference actually has been found. Audiology research in 2008 reported men are 5.5-times more likely to suffer hearing loss than women. After controlling for factors such as noise exposure, smoking, and cardiovascular condition, the study still found men had a higher rate of bilateral and high-frequency hearing loss (i.e both ears and higher sounds). An earlier study found “hearing sensitivity declines more than twice as fast in men as in women at most ages and frequencies.” That study also that hearing decline generally begins for men at age 30, whereas the age varies for women, and age-related hearing loss occurs regardless of low-noise or high-noise work environment.

Regardless of sex or gender, Listen Like a Lawyer previously blogged about lawyers and hearing loss here and here, and recommends to readers to have their hearing tested and get a hearing aid if recommended.

Listening

Beyond hearing, generally accepted definitions of listening involve some form of mental processing and responding. The International Listening Association has adopted a definition of listening that centers on process:

the process of receiving, constructing meaning from, and responding to spoken and/or nonverbal messages.

Detailed research findings on whether the broader listening process differs by gender are summed up by Kittie Watson and Larry Barker in their 2000 book for popular audiences, Listen Up:

Although the literature on cognitive processing suggests there are innate gender differences, most behavioral scientists believe gender differences in listening are more influenced by our cultural socialization than by a biological predisposition.

It seems there are two parts to unpacking that:

- possible innate gender differences in cognitive processing, and

- the behavioral view based on cultural socialization.

The innate differences have to do with brain activity while listening:

Brain research studying hemispheric processing discovered that when men listen they process language using the left hemisphere while women process language through both the right and left hemispheres.

If true, this study suggests implications for how men and women listen:

Since emotions are processed primarily in the right hemisphere, and language in the left, men may not be able to connect words to feelings as easily or effectively as women may.

Watson and Barker go on to summarize further research that because of this left-brain processing, men may be less distracted as listeners because they essentially receive only one message rather than multiple messages. This contradicts some popular psychology claiming men are more distracted listeners—reinforcing the point that overbroad answers to this question are too simplistic. In terms of brain processing and listening, another study cited in Watson and Barker found that men tend to remember the “gist” of the conversation, whereas women tend to recall precise words and phrases.

But the left-brain/right-brain finding is itself subject to dispute. These sex-based processing differences were found in an Indiana University study in 2001 by Phillips et al. But a larger study from two years earlier did not reach the same findings:

[A] larger scale MRI study (50 men, 50 women) concluded that men and women actually do not have substantive differences in lateralization of brain activity or brain activation patterns during a listening task.

This is from Andrew Wolvin’s overview of research in Listening and Human Communication in the 21st Century (2010), citing a 1999 study by Frost et al. (On a related side note, the reliability of pretty much all fMRI research has recently been questioned.)

Listening comprehension

It’s also unclear whether any such processing differences make a difference in actual listening comprehension. Auburn professor Margaret Fitch-Hauser and colleagues did a study of actual listening comprehension—they called it “Listening Fidelity”—where participants were exposed to spoken words and then were tested on their listening comprehension. This study found no difference in listening comprehension among men and women (college students in this case). They also found listening comprehension did not significantly relate to the participant’s self-described listening style. In other words, listeners with a more “people-oriented” preferred style did not perform significantly differently from those whose preferred listening style leans towards information or tasks (more on this in a moment).

The listening process overlaps with working memory, as remembering the message (or not) relates to the listener’s response. A 2016 study of concentration and listening (as well as reading) comprehension reiterated past studies finding no gender differences in working memory. That study by Wolfgramm and colleagues, surveying a group of sixth graders in Switzerland, reached somewhat complex findings on gender. The overall finding was that concentration is a significant factor in listening comprehension, although not so much in reading comprehension. Along the way, the study reached findings that contradicted a perceived gender gap (favoring girls) in reading and listening:

Boys . . . outperformed girls in one of the listening comprehension tests. However, girls scored higher when tested for their ability to concentrate and for working memory but not when tested for vocabulary. This indicates that boys seem to have more problems with bottom-up processing than girls do. Nevertheless, problems with bottom-up processes do not affect boys’ performance in listening and reading. It would seem that boys compensate for their underperformance in concentration and working memory: We presume academic self-concept to be a possible factor accounting for that compensation.

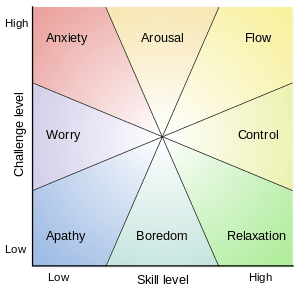

Listening, self-concept, and social status

And this raises the strongly conflating issues of nurture and culture. “Academic self-concept” refers to confidence or anxiety at the task. In the Wolfgramm study, boys had a higher academic self-concept than the girls, and their self-concept compensated for whatever processing differences might exist. This is just one example of how socialization by gender could play a significant role in the question of sex, gender, and listening.

One paper reviewing various studies on gender and stereotypes pointed out that experimental participants listened more carefully when they occupied “low status” roles and were assigned to listen to “high status” individuals. The paper, by Michael Purdy and Nancy Newman, pointed out the connection between status and gender:

There are compelling reasons, according to LaFrance and Henley (1994), why women are usually better at “performing” the nonverbal affective display of listening than men. They link this motivation to men’s “greater social power relative to women in everyday social interactions.”

Listening preferences

As children grow into adult learners, they develop listening preferences which also correlate with gender. Dr. Kittie Watson created a questionnaire that has been used extensively, with survey questions revealing one of the following four listening styles:

- The people-oriented listening style has an external focus on other people.

- The action-oriented listening style prefers an organized approach focusing on the facts and results.

- The time-oriented listening style prefers short and to-the-point statements that do not interfere with other scheduled activities.

- The content-oriented listening style focuses on facts, evidence, and support, and less on who is speaking.

A 2007 study by William Villaume and Graham Bodie found a “rather small relationship” between gender and listening styles. They set out to study the connection between personality (including gender perceptions as one factor) and listening styles by administering a series of questionnaires to college students. Students completed the Listening Styles Profile as well as a questionnaire on their gender role exploring “gender role self-perception” resulting in a “masculinity” or “femininity” score. They also completed a battery of other surveys regarding personality traits, communication style, communication competence, apprehensiveness at communicating and receiving communication, verbal aggressiveness, argumentativeness, and “interaction involvement” such as attentiveness, perceptiveness, and responsiveness.

Villaume and Bodie did find that having an action, time, or content orientation was slightly affiliated with self-reported masculinity score. But people who strongly identified with “feminine” or “masculine” traits both scored higher in terms of people-oriented listening styles. In other words, “people-oriented listening is associated with both high femininity and high masculinity.”

And overall, the gender effect was small, explaining about 5 percent of their study results in light of the other personality-driven factors they included. For example the “Big Three personality traits” measure extraversion (sociability); neuroticism (anxiety); and psychoticism (deviation from social norms). Their study found that Big Three personality differences explained about 9 percent of their study results. The much broader list of personality traits did much more of the work in explaining their study results.

Villaume and Bodie ended the paper with some caveats including the inherent limitation of studying college students. Their comments were not about gender but I think it’s very much about the realities of working as a legal professional:

More importantly, the fact that all participants in this study were university students may affect the nature and strength of the canonical functions derived. These students have not held professional-level jobs with real pressures to get work done efficiently and effectively. It is possible that the listening preferences of these students may change with the added pressures and complexity of professional life after university. This study should be replicated with a sample of adults holding jobs in the working world. It is possible that people-oriented listening may no longer be characterized with all the positive associations reported in this study. Content-, action-, and time-orientations in listening may become more positively evaluated.

Listening skills in the workplace

Other research does look at how working professionals listen and communicate in the workplace. A 2013 paper on working professionals surveyed staff and managers in medium and large organizational environments. In this study, Welch and Mickelson used a “Revised Listening Competency Scale” (developed by Andrew Wolvin and Carolyn Coakley) to evaluate their survey participants on the following types of listening:

- Discriminative listening means listening for auditory cues, attending to verbal and nonverbal signals.

- Comprehensive listening means paying close attention to the actual message.

- Therapeutic listening is emotional listening and letting a speaker “vent.”

- Critical listening evaluates the message to support a decision of accepting or rejecting it.

- Appreciative listening is listening for enjoyment.

Using these dimensions of listening, Welch and Mickelson studied working professionals focusing on two key variables: (1) level of employment (staff, line or middle manager, or senior manager) and (2) gender. Were staff and managers different at listening? At the same level of employment, did men and women show differences?

Their findings are fairly complex. Here are a few takeaways:

- For discriminative listening, the study did not find gender differences among employees at the same level (staff, line and middle managers, and senior managers).

- For comprehensive listening, there were “very large gender differences” for line and middle managers, with women scoring higher. The study found: “Comprehensive listening is a core skill that differentiates managers from staff, and that also differentiates female managers from male managers.”

- There was a moderate difference in genders on therapeutic listening, with women scoring higher.

- There were apparently no significant differences among genders in critical listening at the same level of seniority.

Just an individual’s perception of gender role impacts listening style, Welch and Mickelson pointed out the possibility that male and female managers might relate to their organizational culture differently, explaining some of the differences they found. “Male and female managers might approach their organizational culture with different beliefs about different types of listening,” they hypothesized.

But their more significant findings centered on the listening progression:

[I]ncreased listening competency is associated with more responsibility.

This possibility led them to recommend more study of how listening quality develops over time.

Conclusion

To conclude this tour of the gender research on listening, here is an insight from Melissa Beall’s overview of intercultural listening. She’s quoting an earlier study by Purdy and Newman in 1999, which they presented at the International Listening Association. That study looked at “good and poor listener differences according to gender.” The study reached a finding that resonated:

[T]here were several characteristics that respondents identified as characteristics of good listeners, no matter which gender: eye contact; willingness to listen; shows interest; asks for clarity; gives feedback, and offers advice when wanted.

Thanks to Professors Margaret Fitch-Hauser and Debra Worthington for reading an earlier version of this post.

Sources and links (for non-paywalled sources)

Yuri Agrawal et al., Prevalance of Hearing Loss and Differences by Demographic Characteristics Among US Adults: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2004, Arch Intern Med. vol. 168 (July 28, 2008).

Larry Barker and Kittie Watson, Listen Up: At Home, At Work, In Relationships: How to Harness the Power of Effective Listening (2000).

Melissa Beall, “Perspectives on Intercultural Listening,” in Andrew Wolvin, ed., Listening and Human Communication in the 21st Century (2010).

Margaret Fitch-Hauser, William G. Powers , Kelley O’Brien & Scott Hanson, Extending the Conceptualization of Listening Fidelity, 21 Int’l Journal of Listening 81 (2007).

Laura Janusik, “Listening Pedagogy: Where Do We Go From Here?” in Andrew Wolvin, ed., Listening and Human Communication in the 21st Century (2010).

Michael Purdy and Nancy Newman, “Listening and Gender: Stereotypes and Explanations,” Paper presented to the International Listening Association (2000).

Stephanie Lee Sargent & James B. Weaver III, Listening Styles: Sex Differences in Perceptions of Self and Others, 17 Int’l Journal of Listening 5 (2003).

William Villaume and Graham Bodie, Discovering the Listener Within Us: The Impact of Trait-Like Personality Variables and Communicator Styles on Preferences for Listening Style, 21 Int’l J. Listening 102 (2007).

A. Welch & William T. Mickelson, A Listening Competence Comparison of Working Professionals, 27 Int’l Journal of Listening 85 (2013).

Christine Wolfgramm, Nicole Suter & Eva Göksel, Examining the Role of Concentration, Vocabulary and Self-concept in Listening and Reading Comprehension, 30 Int’l J. Listening 25 (2016).

Andrew Wolvin, “Listening Engagement: Intersection Theoretical Perspectives,” in Andrew Wolvin, ed., Listening and Human Communication in the 21st Century (2010).

Peg Cheng has worked in prelaw advising for more than twelve years, six and a half with the University of Washington (UW) and another six as the founder of her law school admissions consulting company,

Peg Cheng has worked in prelaw advising for more than twelve years, six and a half with the University of Washington (UW) and another six as the founder of her law school admissions consulting company,