According to this study in the Harvard Business Review, lawyers are #1 when it comes to being lonely at work:

In a breakdown of loneliness and social support rates by profession, legal practice was the loneliest kind of work, followed by engineering and science.

(Hat tip to Keith Lee of Associate’s Mind and online lawyer community Lawyer Smack. He wrote more about lawyer loneliness here.)

The legal industry may be particularly prone to loneliness because of the “game face” mentality necessary to represent clients effectively. Putting on a game face on for work can be a professional necessity, but also causes loneliness if it spreads to other facets of life.

People who are lonely often think that everyone else is doing OK while they are not. They think they are the only ones carrying a burden. I have had clients talk about putting their “game face” on rather than sharing truthfully about themselves.

This quote is from British psychotherapist Philippa Perry, board member of a social business called Talk for Health which aims to create a network of long-term peer support systems for meaningful sharing and listening.

Many lawyers and legal professionals and law students already have long-term peer groups in their colleagues and classmates. But if people are gathering on a regular basis with their game faces firmly in place, those peer groups may not be serving a support function at all. Is there anything lonelier than giving a performance that everything is wonderful and there is “nothing to see here”?

Peer groups that provide real support are one of the most valuable ways to combat loneliness. To delve more into the elements of real support, I went to the books—specifically the listening textbook authored by Professors Worthington and Fitch-Hauser of Auburn, Listening: Processes, Functions, and Competency. (I met and talked with them a few years ago and would do so again anytime because they are awesome.) They lay out some helpful categories of listening for social support:

Directive v. non-directiveDirective support provides “unrequested specific types of coping behaviors or solutions for the recipient.” Non-directive support “shifts the focus of control from the giver to the receiver” and lets the receiver “dictate the support provisions. |

Problem-focused v. emotion-focusedProblem-focused support seeks to help the speaker solve a problem. Emotion-focused support seeks to help the speaker work through their own emotions |

To provide effective social support, different strategies are called for at different times and in different contexts. Coworkers who do not know each other all that well are not just going to go out for coffee and start providing open-ended, non-directive emotional support. I recently went to a women’s bar event and heard a white woman explain that she really wanted to “be there” for her minority colleagues, but they didn’t seem willing to open up and share. Someone tactfully pointed out that you can be a good colleague just by being kind and reliable over time. Small talk is not meaningless; by being really interested in someone in a socially appropriate way, maybe a deeper relationship will develop. But no one is entitled to hear another person’s story at work.

Junior lawyers and new law students may seek and crave mentors who give them directive emotional support; I recently overheard a third-year law student lecturing—in a supportive but dominant voice—a first-year student. The 3L forcefully instructed the 1L to stop being distracted by a romantic relationship and focus on school, and everything would fall into place as long as the 1L put priorities where they belonged and made a point of taking this time to do what needed to be done, etc. etc.

This kind of directive advice can feel exactly right for a person who is lonely, unsure of their own path forward and how to be effective, or both. But over time, directive support may become more about the person offering it. Directive support can foster a dependent relationship that just leaves the recipient in an even lonelier place when the “director” is not around. A thoughtful mentor should reflect on their own strategies for providing support. Someone who naturally tends toward directive support should consider mixing it up with non-directive approaches. This means asking more questions, prompting the mentee to reflect and assess what is needed. Ultimately, non-directive listening may help a professional grow and take responsibility for their development.

Assisting someone who appears to be lonely is an advanced communication challenge. Jeena Cho has written about the difficulty lawyers may feel in breaking the cycle of loneliness:

When we feel loneliness, it’s easy to continue on the path to more loneliness rather than to do something about it. It makes sense that lawyers would avoid taking steps to break the loneliness because it would require vulnerability.

Others around a lonely person may be able to sense it and help them break the cycle. Worthington and Fitch-Hauser give an example in their book of the following—something that lawyers and legal professionals may recognize from their own conversations at work:

Person 1: Hey, how are you?

Person 2: Oh hello, I’m fine. How about you?

Person 1: Hmm, you don’t sound like you’re fine. What’s going on?

Person 2: Oh nothing. Really, I’m fine.

They acknowledge that in this scenario, 1 may accept 2’s statement at face value and leave the conversation. But to really go in for the social support, 1 might push for more with something like “Are you sure? Did something happen at work that upset you? If you’d like to talk about it, I’m here to listen.” They acknowledge this is a heavy-handed response and suggest another, less intrusive way to handle the conversation as well: 1 may choose to sit down next to 2 and ask 2 a bit more specifically how work is going. As Worthington and Fitch-Hauser point out, even the heavy-handed approach can be helpful. It’s uncomfortable and possibly annoying, but it provides the potentially lonely person with the opportunity to respond.

Both of these possible approaches also avoid the “negative social support behaviors.” In terms of what not to do, Worthington and Fitch-Hauser list the following:

- Giving advice

- Using platitudes or clichés

- Saying “I know exactly what you’re going through”

- Telling people to stop crying or stop being wrong or embarrassing

- Saying it’s not such a big deal and minimizing the situation

- Blaming the person seeking support

Other than unsolicited and unwanted advice, these should be pretty easy to avoid. It’s much harder to provide truly effective social support. Really good social support tends to be “invisible”: “The recipient isn’t consciously aware that support is being given and, therefore, doesn’t feel any negative consequences of being the recipient.”

I think this observation crystallizes the true art form of helping a colleague break through their loneliness. If they become aware that (1) you think they’re lonely and (2) you are trying to help, your chance of effectively helping them drops precipitously. Stealthy, invisible support using discerning, empathetic listening can encourage someone to begin addressing their loneliness by doing what Jeena talks about in her article: taking a tiny step.

Q: My first question is very basic: What is executive coaching?

Q: My first question is very basic: What is executive coaching?

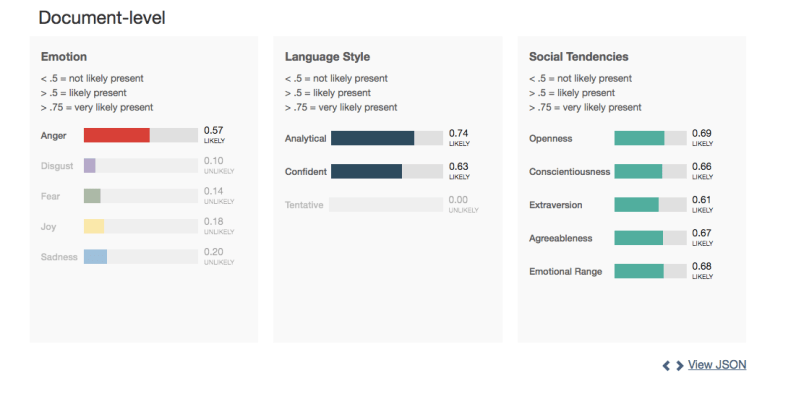

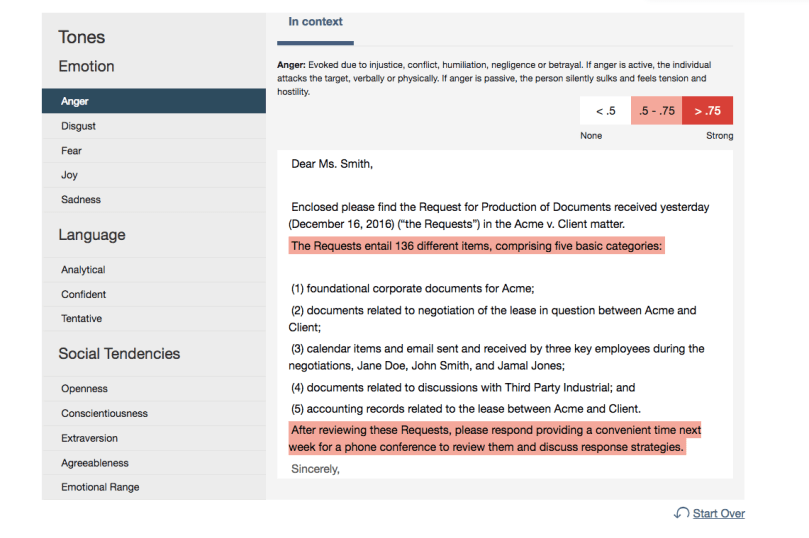

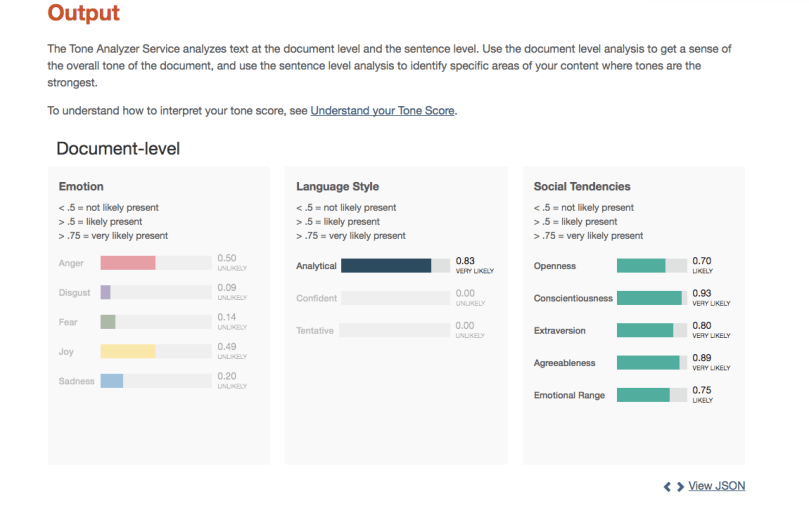

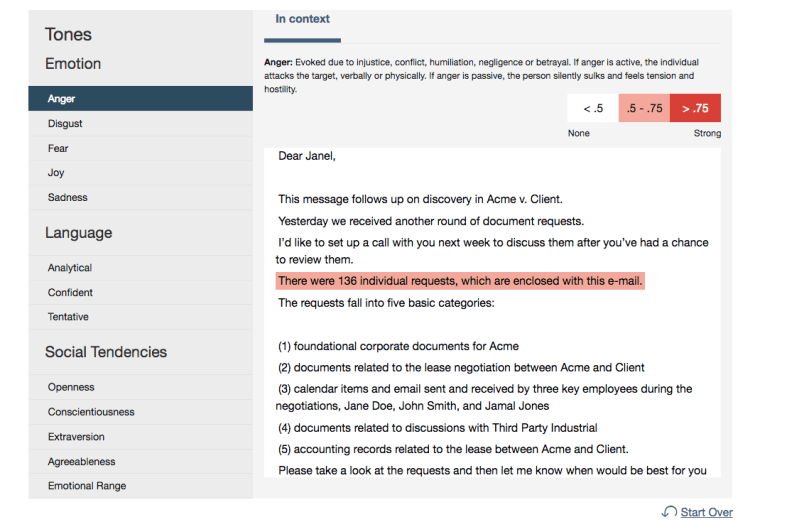

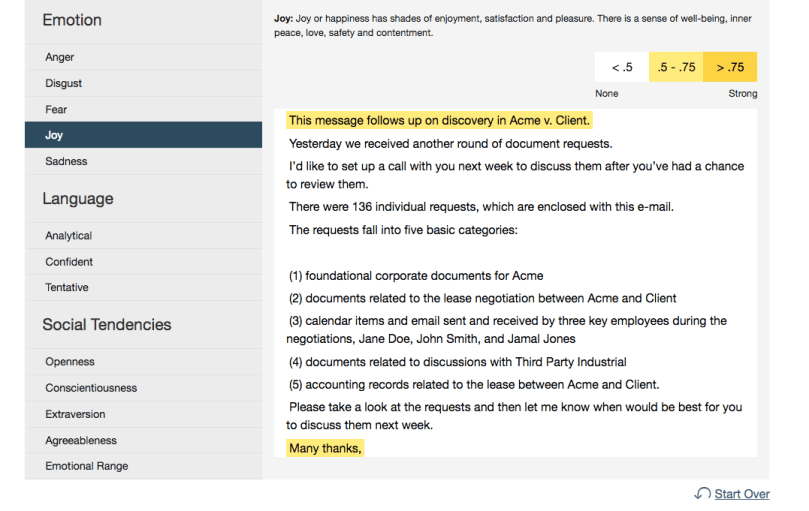

The message did not rank on sadness, fearfulness, or disgust.

The message did not rank on sadness, fearfulness, or disgust.