Listening and speaking can be empathetic. Even reading (reading literary fiction, that is) is connected with empathy. But what about writing? And specifically, what about legal writing? The textbooks concur that writers are supposed to harness not only logos and ethos but also pathos in their appellate briefs and other persuasive writing. But what about the pathos—the emotion—in everyday legal writing?

Ever since learning about IBM’s Watson Tone Analyzer, I’ve wanted to try it on some legal writing. I wanted to find out what a “robot” like Watson has to say about the voice and emotions in contrasting legal-writing samples. Here’s what Watson can do:

The [Watson Tone Analyzer] service uses linguistic analysis to detect and interpret emotions, social tendencies, and language style cues found in text. Tones detected within the General Purpose Endpoint include joy, fear, sadness, anger, disgust, analytical, confident, tentative, openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional range.

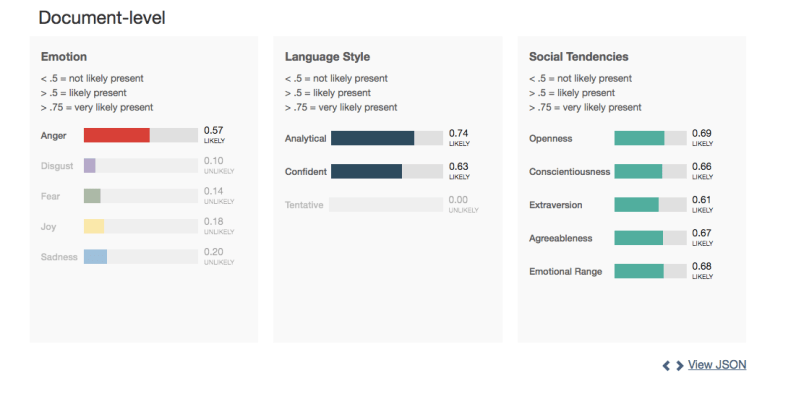

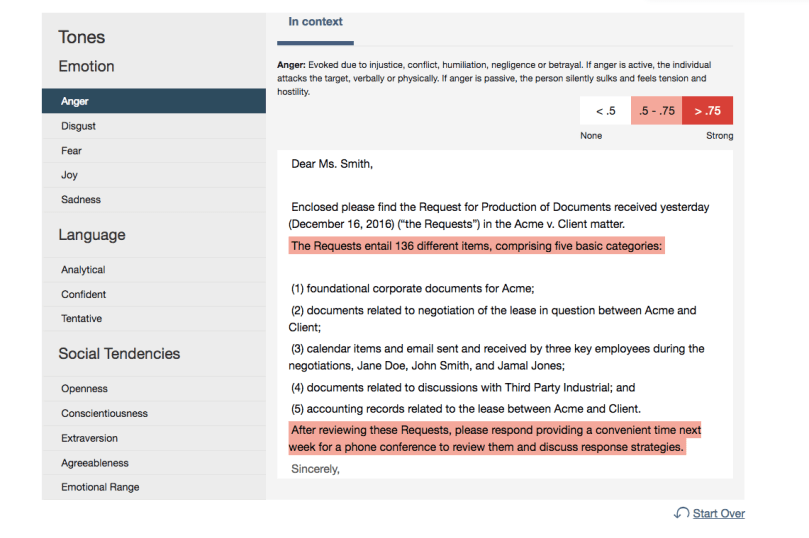

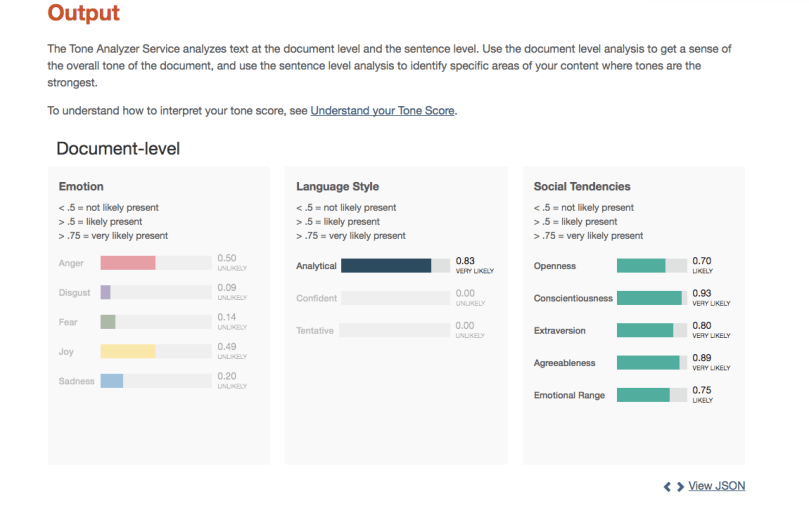

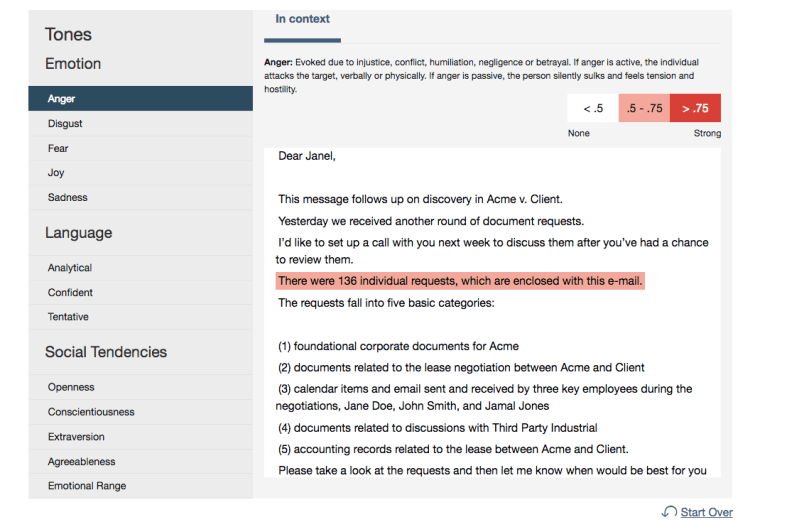

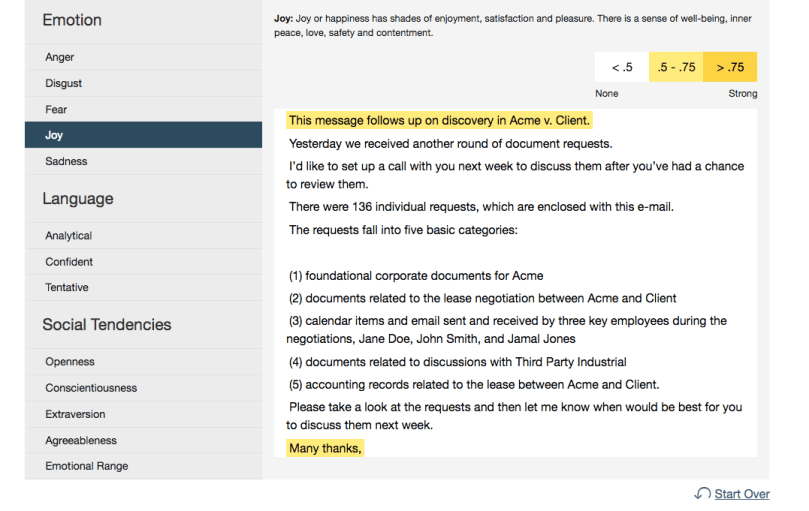

As shown below, Watson offers an overall document-level analysis, and it highlights sentences that score particularly high on certain emotional indicators.

For this exploration, I chose the idea of an email sample because emails should be relatively short. Also, email is so prevalent in law practice. It’s a constant, quotidian part of life for many, many lawyers. Email doesn’t stop to ask, “Is this a good time to talk?” It just arrives. And it can have a major impact on the emotions of the recipient. “”When it comes to emails that are negative in tone, it makes you angry,” Professor Marcus Butts told Time Magazine, in an article about why email puts workers in a nasty mood—especially when checking email after normal business hours. The effect of such emails spills over: “Being angry takes a lot of focus and our resources and it keeps us from being engaged with other things.”

Given email’s potential emotional impact on the daily lives of lawyers, this post explores what the Watson Tone Analyzer had to say about two mocked-up emails. The two versions below both have the purpose of forwarding discovery requests to a client. The first version uses more formal language, and the second more conversational language. What does the Tone Analyzer say about these different versions? And in a more realistic situation, could the Tone Analyzer be useful to lawyers working on their communication skills? Following the text of the two emails, the post compares and contrasts how the Watson Tone Analyzer processed these emails.

Dear Ms. Smith,

Enclosed please find the Request for Production of Documents received yesterday (December 16, 2016) (“the Requests”) in the Acme v. Client matter. The Requests entail 136 different items, comprising five basic categories:

(1) foundational corporate documents for Acme;

(2) documents related to negotiation of the lease in question between Acme and Client;

(3) calendar items and email sent and received by three key employees during the negotiations, Jane Doe, John Smith, and Jamal Jones;

(4) documents related to discussions with Third Party Industrial; and(5) accounting records related to the lease between Acme and Client.

(5) accounting records related to the lease between Acme and Client.

After reviewing these Requests, please respond providing a convenient time next week for a phone conference to review them and discuss response strategies.

Sincerely,

Antoine Associate

Antoine J. Associate

Law Firm LLP

Citytown, RH

Dear Janel,

This message follows up on discovery in Acme v. Client. Yesterday we received another round of document requests. I’d like to set up a call with you next week to discuss them after you’ve had a chance to review them.

There were 136 individual requests, which are enclosed with this e-mail. The requests fall into five basic categories:

(1) foundational corporate documents for Acme

(2) documents related to the lease negotiation between Acme and Client

(3) calendar items and email sent and received by three key employees during the negotiations, Jane Doe, John Smith, and Jamal Jones

(4) documents related to discussions with Third Party Industrial

(5) accounting records related to the lease between Acme and Client.

Please take a look at the requests and then let me know when would be best for you to discuss them next week.

Many thanks,

Antoine

Antoine J. Associate

Law Firm LLP

Citytown, RH

So how did Watson analyze the emotions in these two messages?

Tone Analysis of First Sample:

The dominant emotion in this message was perceived as anger. Indications of disgust, fear, joy, and sadness were “unlikely.”

The sentence-level analysis indicates that the anger emanates from plain, descriptive language (what the requests entail) and the final request (“please respond…”). The pink highlighted sentences below were flagged as moderately angry wording:

The language in this message was viewed as both analytical and confident, but not tentative. The analytical content is highlighted here in blue, with the dark blue being more intensely analytical than the light blue:

Interestingly, the confidence score appears to come solely from the signature block containing the words “Law Firm.” (The same is true of the second sample, where “Law Firm” were also the only text flagged for confidence. But the second sample’s overall confidence score at the document level is 0.00 (unlikely) compared with .63 (likely) for this first sample. More on that later.)

The same text can be studied in more depth for its social tendencies including openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional range. For example, the language “Enclosed please find” was ranked as conscientious but not open, extraverted, or agreeable. That language also scored high on emotional range. That same language was also flagged for showing anger.

Among the five items in the email’s numbered list of documents, item (3) seemed to be an emotional hot spot for Watson, scoring relatively high on all five of the emotional parameters. This result was notable because item (3) is the only item in the list that included individual people’s full names.

Here are the metrics for agreeableness, which form an interesting contrast with the second sample below. The greeting and sign-off are in light green, indicating moderate agreeableness. The only line with strong agreeableness was that same item (3) listing calendar items and emails sent by specific individuals by name. (In contrast, the second sample below tried to be friendlier and succeeded, as indicated by the more strongly agreeable opening and closing passages.)

Tone Analysis of Second Sample

The second email was meant to be more friendly. What it accomplished, according to Watson, was slightly lessening the anger score and raising the joy score. The joy score is still “unlikely,” but it’s at .49 instead of 0.18 in the first sample. Although it’s less angry and more joyful, it also completely lost its confidence score.

Despite the overall attempt to use friendlier language, anger still emanated from the email, specifically the sentence enclosing the discovery requests:

But joy came from the revised beginning and closing words:

The message did not rank on sadness, fearfulness, or disgust.

The message did not rank on sadness, fearfulness, or disgust.

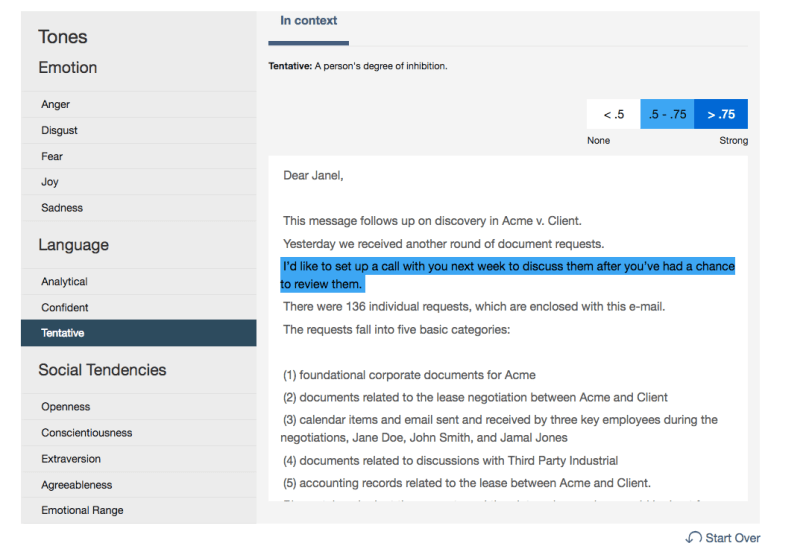

Watson’s evaluation of the language looks for analytical, confident, and tentative language. The more informal email’s language was also measured as analytical and confident, like the more formal first sample. Unlike the formal sample, it was also somewhat tentative. The source of this tentativeness was a sentence about what the writer “would like to do”:

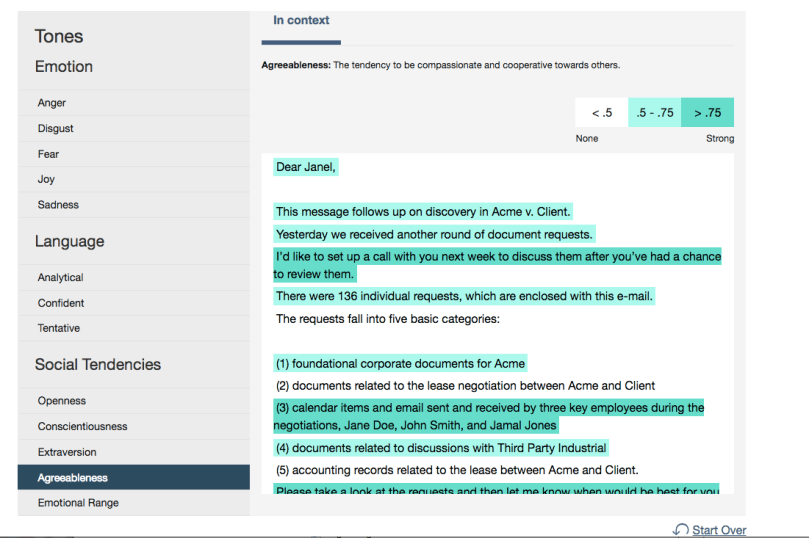

Not surprisingly, that same sentence was also ranked as agreeable:

Quantitatively, the informal sample contained more agreeable language, ranking 0.89 on agreeableness compared to 0.67 for the first sample.

Conclusion

What did I conclude from analyzing these two samples using Watson’s Tone Analyzer? Like many AI analysis, it seemed to confirm what I think I already know.

- Legal information is not inherently happy, at least not in a litigation setting. The most “angry” language in both messages was the language simply describing the scope of discovery.

- Language that is more tentative and less confident may also be more agreeable. This correlation raises many questions: does tentative language compromise clarity? If so is it worth it to sound more agreeable? Different writers, readers, and situations will of course require different decisions.

- Watson’s Tone Analzyer may be helpful to some writers on a limited basis. As with any computer analysis of language such as Flesch-Kincaid readability scores, writers should ask whether the computer analysis could help them. I don’t see legal writers building Watson’s Tone Analyzer into a checklist for every email. But it could be a worthwhile exercise just on a couple of messages, to see what predominant tone Watson diagnoses.

And as with any computer analysis of language, take it with a grain of salt. I tested Watson on litigators’ favorite nastygram conclusion:

“Govern yourselves accordingly.”

The results are below but here’s a summary: Its predominant language was sadness (?????). Its most notable social tendencies, according to the Tone Analyzer, were extraversion and agreeableness.

The “govern yourselves accordingly” analysis notwithstanding, a “robot” such as the Tone Analyzer could create an interesting exercise for trying different words and seeing how they measure. So . . . govern yourselves accordingly.

Note on use of Watson: these screen shots were taken on April 25 and 26, 2017. The metrics appear to have changed slightly from tests about six months earlier on identical language. Thus a final lesson is to know your tool and stay updated. Make sure you’re comparing apples to apples if relying on quantitative analysis of language.

Many thanks to Gail Silverstein, Clinical Professor of Law at the UC Hastings College of the

Many thanks to Gail Silverstein, Clinical Professor of Law at the UC Hastings College of the

Thanks to Lainey Feingold for this guest post. Lainey is an author and disability civil rights lawyer. Her book,

Thanks to Lainey Feingold for this guest post. Lainey is an author and disability civil rights lawyer. Her book,  In writing my book about Structured Negotiation I was introduced to a book that proved crucial to my thinking about the work my clients and I had done for two decades:

In writing my book about Structured Negotiation I was introduced to a book that proved crucial to my thinking about the work my clients and I had done for two decades: