This guest post summarizes the authors’ presentation, “Beyond Words: What Business Schools Can Teach Us About Non-Verbal Persuasion” at last week’s Association of Legal Writing Directors Biennial Conference held at the University of Minnesota Law School.

By Erin Carroll, Georgetown Law, and Shana Carroll, Northwestern University Kellogg School of Management

The practice of law places great emphasis on words. Yet, how we communicate transcends words. Studies confirm that when we (lawyers and non-lawyers alike) speak, our tone, volume, pace, stance, gestures, and expression may convey more to our listeners than the words we use.

Most law schools teach oral presentation skills during the 1L year in the context of the appellate argument or the meeting with the supervising attorney. But often these skills are afterthoughts to a focus on written work. And even in teaching these skills, professors may unduly home in on the substance of arguments rather than on the way they are delivered and how listeners receive them.

Most law schools teach oral presentation skills during the 1L year in the context of the appellate argument or the meeting with the supervising attorney. But often these skills are afterthoughts to a focus on written work. And even in teaching these skills, professors may unduly home in on the substance of arguments rather than on the way they are delivered and how listeners receive them.

Given the realities of legal practice, law schools would do well to conceptualize presentation skills more broadly. Law professors should consider the range of situations in which students will present and how those presentations could be more effective, putting aside their substance.

Business schools can serve as a model. Business school curriculums generally recognize that innumerable interactions in the working world are indeed presentations. Pitching clients, negotiating deals, running an effective meeting, and reviewing employees, for example, qualify. They all offer opportunities for speakers to consider and shape how they want the listener to understand their message.

This is no less true for lawyers. Lawyers—at least those in the private sector—are also businesspeople, bringing in clients, doing deals, and interacting with colleagues. Public sector lawyers, too, negotiate, interview, and supervise. Interactions that fall into any of these broad categories can be bettered by adroit presentation skills.

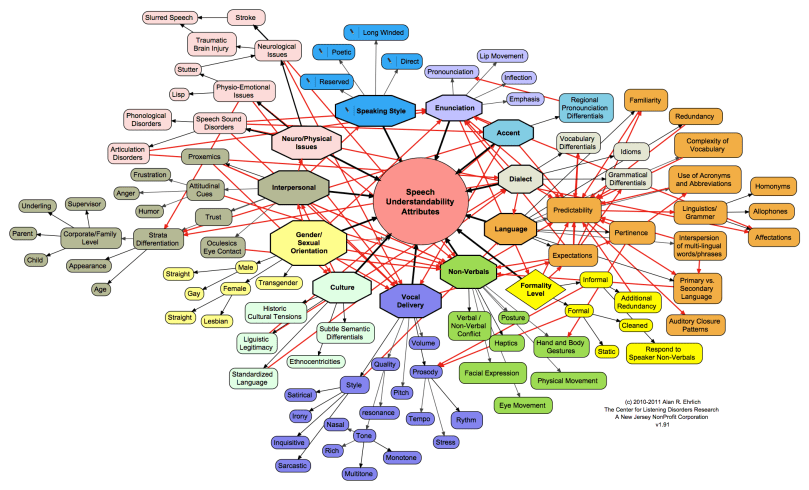

Accordingly, we urge our business and law school students to think about how they can use their voices and their body language to drive home their intended meaning. That means focusing on volume, pace, tone, emphasis, stance, and an array of other paralinguistics (the qualities of how something is said rather than what is said) as well as gestures and expressions.

First, to familiarize our students with the multitude of means by which we communicate to our listeners, we have done the following exercises:

- Ask students to find a video of a speaker they find particularly effective or ineffective. Have them post the video to a discussion board along with a description of why that speaker was effective or not. To the extent a student’s description is generic, press the student to substantiate it by indicating particular paralinguistic qualities or aspects of body language.

- Alternatively, have students watch a video in class, identify these qualities, and discuss them. We have used this video of the 1992 presidential debate between Bill Clinton and George Bush, and this video of a press conference given by Tony Hayward, the former chief executive of BP, just weeks after the Deepwater Horizon explosion.

For either exercise, create a list of the different paralinguistic qualities and aspects of body language that can impact meaning. These could include: volume, pace, inflection, facial expression, movement, and fluidity. Professors might also discuss the importance of congruence between body language, paralinguistics, and message in conveying meaning.

In our classes, once students have some comfort with identifying and critiquing the presentation skills of others, we give them the opportunity to experiment. Here are a couple of things we suggest:

- Start with a quick, kinesthetic exercise that gets students to hear the range of sentiment their voices can convey and see how their body language can impact meaning. We accomplish this by asking students to pretend they are ordering a ham sandwich. Students line up around the perimeter of the classroom and one by one come up to a podium at the front. Once they get there, we shout out a descriptive word like “despondent,” “angry,” “elated,” or “frustrated.” Students must then try to express that emotion when they say the following sentence: “I would like a ham sandwich with the works.” All sorts of sentences could be substituted here, but we like that this exercise uses something that feels a bit silly as a means of easing nerves.

- Students are then ready to try out those same skills in a more serious scenario. Pass out slips of paper that include a couple of sentences that students might actually say in an upcoming presentation. For example, if oral arguments are approaching, short excerpts from student briefs could be used. Once students have their “script,” they get a couple of minutes to prepare to present it. During that time, students can think about what meaning they want to convey to the listener and how they can use volume, pace, tone, emphasis, gestures (and any other skills the class has discussed) to best do it. Students could be encouraged to experiment with different variations to identify which approach works best given their objective. They could also be placed in pairs or small groups and allowed to practice and get feedback from one another. Students could then be asked to volunteer to share their version with the class.

Of course, there are many, many other exercises that emphasize paralinguistic and nonverbal communication skills. These could include, for example, exercises on articulation or stance. What will be most helpful depends, of course, on the students’ and professors’ goals.

Regardless, law professors should keep in mind just how broad presentation skills are, how often students will use them in practice, and the variety of ways to teach them. We want to ensure that we are helping students improve their ability to persuade beyond simply teaching them to make a well-reasoned argument.

But what might be news are the details of these students’ individual experiences or the scope of these negative experiences within a student body. This matters because a precursor to making a law school more inclusive is understanding how students are feeling excluded. It also matters because if you’re not hearing those details, you might think that your school doesn’t have an inclusion problem. Or worse, you might be unknowingly contributing to it.

But what might be news are the details of these students’ individual experiences or the scope of these negative experiences within a student body. This matters because a precursor to making a law school more inclusive is understanding how students are feeling excluded. It also matters because if you’re not hearing those details, you might think that your school doesn’t have an inclusion problem. Or worse, you might be unknowingly contributing to it. Research suggests that the differences or misunderstandings that divide us can be lessened when we speak to each other and get to know each other a little more. Inviting students to share their stories and listening to those stories can improve those students’ well-being, especially if they feel that they haven’t been listened to in the past.

Research suggests that the differences or misunderstandings that divide us can be lessened when we speak to each other and get to know each other a little more. Inviting students to share their stories and listening to those stories can improve those students’ well-being, especially if they feel that they haven’t been listened to in the past.

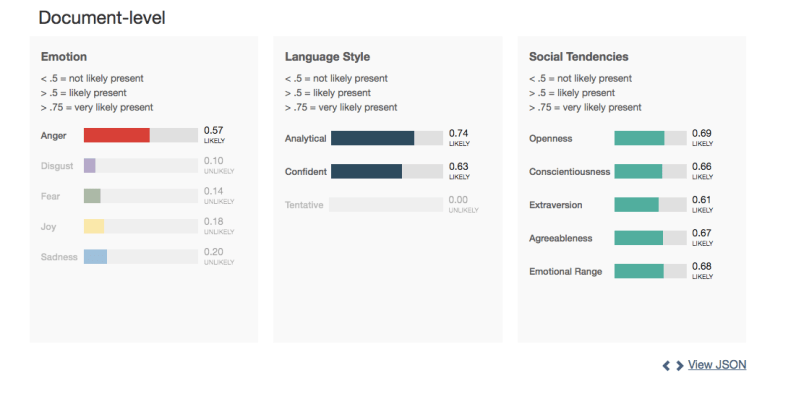

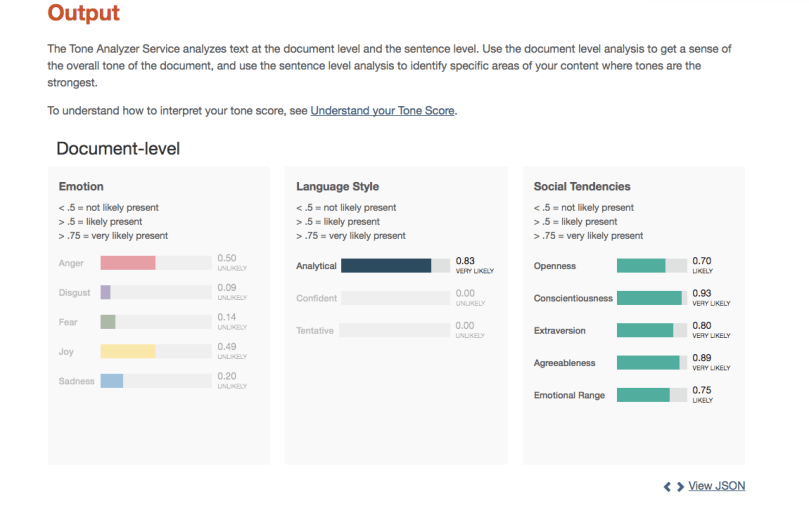

The message did not rank on sadness, fearfulness, or disgust.

The message did not rank on sadness, fearfulness, or disgust.